Static Page Generator and HTTP Server from Scratch with 0 Dependencies in Elixir

What we’ll see in this series of posts#

- Create our HTTP server

- Read requests and display results

- Respond concurrently

- Transpile Markdown to HTML

- How to create templates to include CSS and other elements

What is a static site generator?#

Writing blogs directly in HTML and CSS can be time-consuming, especially for complex sites. While this website itself uses very simple HTML (by design), imagine a blog with multiple links, tags, multi-level menus, etc. Things can get complicated quickly.

Static Site Generators solve this by allowing us to write posts in Markdown, which is simpler than HTML. The generator then converts them into HTML and applies styling with CSS. Static pages are delivered to the client without any server-side logic beyond serving content.

Popular Open-Source Options#

- Serum

- Franklin

- Gatsby

- Hexo

- Eleveny

- Pelican

- Zola

- Hugo (this website)

- Jekyll

Mine is a simple project called Personal.

Personal#

This project lasted about a week, inspired by boot.dev and ThePrimegen, where they push you to build interesting projects from scratch. I decided to do it with zero dependencies for added challenge.

By building it myself, I gained an appreciation for open-source libraries that handle these problems efficiently.

HTTP 1.1 Server#

As we’ve said, we’re going to program this from scratch. So the first step is to open sockets. We’ll use the gen_tcp module, which will give us everything we need to set up our server.

I won’t go into much detail about how an HTTP server works, but the first thing we need to do is bind to a port and obtain our “Listen Socket”

1 defp accept(port) do

2 {:ok, listen_socket} = :gen_tcp.listen(

3 port,

4 [

5 :binary,

6 packet: :line,

7 active: false,

8 reuseaddr: true,

9 nodelay: true,

10 backlog: 1024

11 ]

12 )

13

14 Logger.info("Listening port: #{port}")

15

16 loop(listen_socket)

17 end

This interacts with the TCP/IP stack where a buffer of 1024 spaces is created for pending connections (backlog). To understand this a bit better, every time someone makes a request to our port, it is stored in the buffer waiting to be accepted. Reducing or increasing this number dramatically affects throughput. (You can run benchmark tests and you’ll see the difference :3)

As I just explained, we have a buffer, but now we need to accept these connections one by one, which will be removed from this buffer. To do this, we need to execute the following code in an infinite loop.

1 defp loop(listen_socket) do

2 case :gen_tcp.accept(listen_socket) do

3 {:ok, socket} ->

4 Personal.Worker.work(socket)

5

6 {:error, reason} ->

7 Logger.error("Failed to accept connection #{inspect(reason)}")

8 end

9

10 loop(listen_socket)

11 end

It’s very important to consider concurrency at this point because if we think about it, we have

a function running in an infinite loop with :gen_tcp.accept/1 and Personal.Worker.work(socket), so

if these functions are slow, we can imagine the massive bottleneck in accepting requests. Ideally, we want to accept connections and serve them in parallel without one blocking the other.

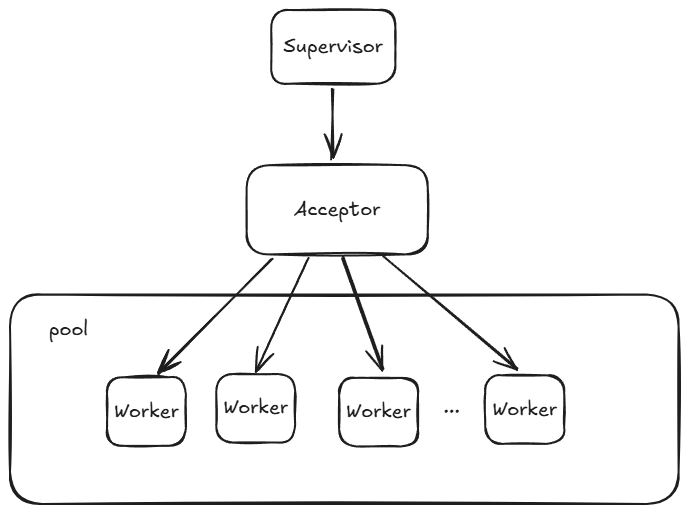

So at this point, we need to consider the architecture of our server. Something similar to this:

In my case, it’s not exactly like this since I don’t create a pool, I simply launch processes. The important thing to highlight

here is that we have a Process called Acceptor that accepts connections, and the Worker will be responsible for creating a process per connection to serve the request.

Here we see the main code of the worker:

1 def work(socket) do

2 fun = fn ->

3 case :gen_tcp.recv(socket, 0) do

4 {:ok, data} ->

5 {code, body} = handle_request(data)

6 response = "#{@http_ver} #{code}\r\n#{@server}\r\nContent-Type: text/html\r\n\n#{body}\r\n"

7 :gen_tcp.send(socket, response)

8 :gen_tcp.close(socket)

9

10 {:error, reason} ->

11 Logger.error("Failed to read socket socket #{inspect(reason)}")

12 :gen_tcp.close(socket)

13 end

14 end

15

16 pid = spawn(fun)

17 :gen_tcp.controlling_process(socket, pid)

18 end

Our Acceptor only executes the fun declaration, creates another process with spawn/1, where we pass

the fun and tell the stack using :gen_tcp.controlling_process(socket, pid) that the socket we obtained by accepting with :gen_tcp.accept now belongs to the process we just created.

So our Acceptor can continue its loop accepting connections, and the new process will continue serving the request.

As a note, I have to add that this is not the best way to handle this problem since we raise processes without any type of control, and the fun declaration is executed at runtime, which can cause problems depending on the use case.

The real world is much more complex, and the reality is that we end up using third-party libraries. In the case of Elixir, these libraries are usually:

- Ranch used by

- Cowboy used by

- plug_cowboy used by

- Plug used by

- Phoenix.

- (I could continue)

Moreover, now we have new libraries like Bandit that also has it’s own dependency tree

These libraries are examples of how to work in production, but our small project serves to help you understand why these libraries exist and why people maintain them for so many years.

HTTP 1.1 Request#

Great, now we have the client’s socket where we can read and write data. Now we can work in the world of Requests.

HTTP requests are quite simple, as we obtain them in plain text where we can receive multiple lines separated by line breaks.

An example of a request without headers would be:

GET /styles/style.css HTTP/1.1\r\n

It’s now our problem to read the line, parse it correctly, and know what to do with it. In this case, we can see it’s a GET request wanting to obtain the stylesheet at the indicated path.

In our case, I’ve only implemented GET

1 def handle_request("GET " <> rest) do

2 path =

3 rest

4 |> String.split(" ")

5 |> List.first()

6

7 body = FileReader.get_file(path)

8

9 if body == nil do

10 {"404 Not Found", ""}

11 else

12 {"200, OK", body}

13 end

14 end

15

16 def handle_request(_) do

17 {"405 Method Not Allowed", ""}

18 end

As we can see, we extract the path, look it up in FileReader, and return an appropriate response. NOTE: it’s very important how we read the data because this can generate very serious security flaws. In the case of Personal, we’ll see that it pre-caches files in memory.

To send data, we just need to follow the Response format similar to this:

1response = "#{@http_ver} #{code}\r\n#{@server}\r\nContent-Type: text/html\r\n\n#{body}\r\n"

And finally execute

1:gen_tcp.send(socket, response)

2:gen_tcp.close(socket)

These last two lines send the response and close the socket, thus ending the execution of the socket’s controlling process.

As we can see in this simple case, there are thousands of things missing here, such as header handling, different HTTP requests, etc. There’s a world of specifications to discover! rfc9110 have fun!

Getting the body!#

The objective of any HTTP server is for our client to obtain any type of data we want to make visible, but this must be done securely. Imagine someone could do something like GET /etc/passwd and our server says, “Sure, no problem, here you go…”.

To avoid this, and knowing this is a small blog, I’ll directly prevent GET requests from having to make system calls to read. To do this, when the server starts up, it will read all data from a specific folder and generate a data structure to access it.

In our case, FileReader defines a folder I’ve called static that stores all the final information our blog can offer. At the same time, the folder structure will be the same as the HTTP request structure.

For example, if our structure looks like this:

static/

├─ images/

├─ styles/

│ ├─ style.css

├─ blog/

├─ index.html

To obtain style.css or index.html, the requests should be:

GET /styles/style.css HTTP/1.1\r\n

GET / HTTP/1.1\r\n

In the case of FileReader, it builds a Map where each key is a folder and the files inside this folder have the filename as the key and the file content as the value.

1%{

2 "static" => %{

3 "images" => %{

4 "sample.webp" => <<82, 73, 70, 70, 214, 10, 0, 0, 87, 69, 66, 80, ...>>

5 },

6 "index.html" => "<html>...</html>",

7 "styles" => %{

8 "style.css" => "/* css content */"

9 }

10 }

11}

So if in the data variable we have the previous map, to obtain sample.webp we would execute:

1data["static"]["images"]["sample.webp"]

In my opinion, this method is quite simple. Obviously, if the script that builds this map accesses resources outside of static, we would have a problem. But apart from that, once the structure is written, it cannot be updated until the server is restarted (although it can be changed at runtime).

In my case, the structure is stored in a persistent_term which offers the fastest reads in Elixir after declaring variables directly in code.

With this, the HTTP server part ends. In the next post, we’ll see how we build HTML from Markdown and how we do the “bundle” to the “static” folder.

This has been translated to english with Claude from the original Spanish post